Discarding Magic Feathers - Going Frameworkless in Scala

A good few years back, I looked into building a Scala webapp using Java's little-known provided HTTP server rather than one of the many frameworks already out there during my 10% time at Springer Nature.

I made a mistake here - to avoid those frameworks I built my own framework to route requests within a webapp. I called it Sommelier, and it is now hidden away in a private github repo as really, we don't need another of those.

Maybe we don't need any of them at all.

TODO MVP

A year or so later, my then-colleague David Wickes launched TODO MVP.

The objective of this project is to demonstrate that it is relatively simple to build web applications using HTML, CSS and a small amount of server side code written in a language of your choice.

Once again on a Springer Nature 10% day I decided I'd have a go at this in Scala, this time without any kind of framework or library, homebrewed or otherwise.

This article

It's taken me over three years to get round to finishing this article (which I promised to several people would be coming soon at the time!). This is largely because my first couple of attempts were technical deep-dives with lots of code examples.

I finally got round to completing this when I realised that not only was that completely unnecessary, but that a deep-dive would undermine my central points - that this is not hard to do, and that a core reason to do it is to learn, which is best achieved in the doing.

So there will be very few code samples in here, but I will link to the appropriate places in my github repo in each section.

Building a Scala app without a build tool

Building a Scala app with the intention of not using any of those frameworks with their obscure syntax and unnecessary concepts and then going on to build it with SBT would be kind of perverse. I could use Li Haoyi's excellent Mill, and I have been doing both in professional and personal projects, but given the nature of this project I wanted to see what I could do without.

My first instinct was to go to Make, though I knew almost nothing about it. The only times I've had to edit a makefile have been when building a third party app or library from source that inevitably fails for some environmental reason.

At the time, there were no instructions that I could find on how to do this (there are now - https://github.com/jodersky/scala-makefile), so I also had to go to first principles and learn a bit about make and a bit about scalac.

make is pretty straightforward, at least to the extent needed for what I was building, so was mostly about learning the syntax to run CLI commands that I had already prepared.

I created 6 commands that roughly map to what you expect in build tools:

compile- create abindir, then invokescalacclean- remove all dirs created by invokingmaketasksdeps- no, not a heresy in this context! Just pulls the Scala lib JAR from a public repo and places it in alibdirassemble- creates adistdir using the contents ofbinandlib, then usesjarto create a "fat" application JAR filerun- run the compiled app usingscalatest- run the unit tests usingscala

Apart from make syntax, I had to learn:

- how to pass the right classpath to

scalacandscala(very easy when you're not using any libs, but also pretty straightforward when you are) - the structure of a "fat" JAR that can be executed stand-alone and deployed easily into a cloud environment

- how to use

jar.

These are all things that had been done for me in the past by tooling. To me this is one of the prime reasons to take on a project like this - getting a better grasp of the fundamentals and understanding what problems the tools you use are solving.

In this case I have a Makefile of just 31 LOC including whitespace, all of it fairly easy to understand. That's not comparable to a build.sbt, as in this case it isn't just the config for the project, it's also doing what SBT would be doing for me, and without the overhead of SBT's dozens of MB of JAR files and the launching of a JVM.

IDE integration (part 1)

This is where a 3rd party build tool has an advantage - if you're using an IDE like IntelliJ chances are there is a plugin that can read that build tool config and set up the environment just right.

With the library-less approach, you're on your own with configuring your IDE. That said, it isn't a big task, and it's not something you typically have to do every day. And once again, you will probably learn something.

Testing a Scala app without a test framework

As a TDD advocate, the first thing I have to be able to do once I can build an app is write (failing) tests. There are a number of test frameworks available to Scala which leverage language features to create rich assertion DSLs, often with a high cost at compilation time. I'd already tired of these long ago and started using the much simpler µTest (also by Li Haoyi), but that's off the menu today as well.

I have previous when it comes to this - one of the standard little projects I like to give myself when learning a completely new language is to write my own test framework, as you can learn a lot from doing so.

Fundamentally, you need:

- a simple mechanism for running the tests in your project

- the ability to make assertions

- easy-to-read feedback that tells you which test(s) failed

Point (2) is usually available in a language's standard library. Java and Scala come with assert, which will throw an exception if a provided condition is not met.

When it comes to running tests, there is no magic - tests are code, and we know how to run code. You need a main method, and in the case of Scala an object extending App will do, and it needs to invoke your tests. You could do this by laboriously instantiating each test class and invoking each test method, printing a test name beforehand, but this would scale poorly and be error-prone.

Instead, you can look for Scala files in your source directory whose name matches a pattern (e.g. _.endsWith("Tests")), load them with the thread's ClassLoader, and treat these as test suites. Then for each of those, ask it for its methods and invoke each with the instantiated suite class. Beforehand, print out the name of the suite and the method about to be invoked so you know what's going on. If any test fails, ensure you exit with a non-zero status code for the sake of automation (e.g. CI).

This would cover the basics, but another extension worth considering would be running all of the tests, gathering the results, and reporting them back at the end, rather than failing fast with an AssertionError. I prefer this approach to failing fast, as tests should always run fast anyway and the more feedback you get the better.

It's also fairly trivial to implement the calling of setUp and tearDown methods for each test, just a few extra lines of code.

Running the tests from the command line (or from within make) is as simple as calling scala with the correct classpath and the name of the test runner class.

IDE integration (part 2)

Again, a typical IDE is unlikely to be able to distinguish custom test code and know how to execute it, though running a Main class should be straightforward.

I made this even more difficult for myself by deciding to have the test suite classes directly alongside the production code in the manner of golang. There is nothing inherent to Java or Scala about where your test code goes, the conventions in use are dictated and enforced solely by the build tools and frameworks (and to some extent, IDEs) we use, so I took the opportunity granted by the freedom of ditching those to use a different approach.

Indeed, there is also nothing set in stone about the use of src directories, language-specific subdirectories or resources directories either, and I have no problem palcing static webapp resources right next to the code they are most related to.

Handling HTTP in a Scala app without a web framework

As a fan of the outside-in approach to testing, now that I can run tests I need to be able to interact with the webapp like a client in order to write my first, failing, acceptance test.

HTTP client

Here's where Java's little known java.net.HttpURLConnection (lovely consistent treatment of acronyms there) comes in.

It does exactly what we need - sends a request and receives a response - but in a bit of a verbose, very Java-like, way with some handling of Input/Output streams. If you want to make HTTP requests often you're going to want to wrap this anyway, and if you're a Scala fan you're going to want to wrap it all the more.

Exactly how you wrap it should depend on your use-case - otherwise, you're practically designing a framework and we don't want that, do we? So if you know you're just dealing with text bodies, make it work conveniently for those - many 3rd party HTTP libraries strive for being completely generic in order to suit as many clients as possible and as a result our code often has to jump through startlingly obtuse hoops to do what should be very simple, most commonly by being needlessly asynchronous and streaming. So take the opportunity to keep things as simple as possible (but no simpler).

HTTP server

Now that the HTTP client is in place, the first acceptance test is written and failing for the right reason - there is no server listening for requests. Time to rectify that.

(aside: HTTP frameworks often come with test "helpers" which allow you to exercise individual routes without spinning up an HTTP server and mounting them all. In my experience these range from next-to-useless to actively misleading - routes themselves should contain minimal logic, routing DSLs implement an order of precedence, and there is a lot of code between the server receiving a request and the routing logic being exercised. All sorts of bugs can be missed by not testing the full routing logic with a real HTTP request)

We're back in Java land now with com.sun.net.httpserver.*, and will once again be hiding the gory details with some more Scala-like wrapping code. This time I'll walk through some portions of the code - it isn't especially complex, but there are some design decisions which may be enlightening.

The TODO list app I'm building requires multiple endpoints, so it needs to support a way of routing requests to the appropriate place. I also want the Scala wrapper of the Java-like code to have a clear responsibility and not mix application of routing logic in with everything else.

I chose to do this by creating the server context only on / and having a function of Request => Response (custom case classes) that will be used to handle all incoming requests:

object Server

{

def start(port: Int, route: (Request) => (Response)): HttpServer = {

val server = HttpServer.create(new InetSocketAddress(port), 0)

server.createContext("/", (exchange: HttpExchange) => {

// build a request from the exchange

val res = route(req)

// apply the response to the exchange

})

server.setExecutor(null)

server.start()

server

}

}

The implementation of Request => Response can adjust behaviour based on the attributes of a Request (HTTP method, path, etc.):

def route(req: Request): Response =

(req.method, req.uri) match {

case ("GET", Static(filename)) =>

// load a static resource and return as the response with apt. headers

case ("GET", "/") =>

// return the app main page

case ("POST", "/") if Form.values(req.body).get("delete").isDefined =>

// handle the case when a form is POSTed to delete a TODO

case _ =>

// response when there is no match - i.e. appropriate 4XX

}

val Static = """\/static\/(.+?\.(?:css|js))""".r

Basic Scala can be leveraged to make this quite clear without using or inventing a DSL, by making use of pattern matching with guards, tuples and regular expressions.

In general we write much smaller apps these days, which should not require complex routing logic, but even when they do basic Scala goes a long way.

Frontend in a Scala webapp without a framework

Server-side

I'm a strong believer in providing simple, functional HTML pages which are only progressively enhanced with CSS and JavaScript, so to me server-side rendering of HTML is the starting point.

As the app is not very advanced, simple Scala String templating was good enough. I did have to write some code to perform HTML-escaping, but this the kind of well-understood and easily implemented function that is just a few lines of code and really not worth pulling in a dependency for.

Client-side

My focus has been on the Scala-side of building a frameworkless webapp, so I won't go into detail here, but I did extend the principle to not using any dependencies for the JS and CSS enhancements of the front-end.

Again this makes things very lean, in terms of page weight and the build process of the app, and JS/CSS and browser standards have advanced a lot in the past decade making this easier than it once would have been without 3rd-party assistance (not that there aren't still many wrinkles - never let it be said that front end development is simple!).

Database access in a Scala app without an ORM / DB framework

I didn't do anything with a DB, relational or otherwise, in building this but it was a question that came up when I first presented this back to my colleagues at the end of a 10% day and worth briefly addressing.

HTTP-accessible document stores

If you're using a document store accessible via HTTP, everything that has come before holds true and you can use the home-wrapped HTTP client to interact with it, extending as necessary (e.g. for authentication).

Relational DBs

Do not fear raw JDBC!

I have experience writing a real production app in Scala which writes to and reads from two tables in a Postgres database, using raw JDBC. Even without crafting a Scala wrapper there isn't as much boiler plate or general faff as I feared there would be. In this instance you would need one dependency, which is the Postgres driver lib.

This probably doesn't scale very well, but it's a long time since I worked with something other than a legacy monolith that had to handle dozens of tables mapped to objects and leverage the kinds of advanced features that ORMs can provide.

I also generally find that either there is as much code/config when using any relational DB library as there is with raw JDBC, or it depends heavily on convention/Magic.

My inclination these days is to start with raw JDBC and introduce a lib as necessary.

Other

Some types of database have different communication protocols, and it's almost certainly best to use their provided client libs, but for the sake of learning, look into those protocols and have a go at implementing a client yourself! You will learn something about the database, and quite possibly learn a lot about the standard library of the language you are using.

Some data stores also provide client libs which are ultimately just a wrapper around HTTP comms. Again, it's worth diving in and looking at what those comms are to discover just how complicated it really is. You might find it trivial enough to forego the library and you will at least learn something.

Dependency injection in a Scala app without a DI framework

Dependency Injection is not magic. You should almost never need a DI framework anyway, especially for a reasonably sized service, and you certainly do not need to roll your own way of ensuring classes are wired up with dependencies.

- Use constructors. Wire up your app only once.

- For unit testing, directly inject mocks / stubs / real instances as you prefer.

- For e2e testing, use your full app with fake external dependencies, and config which points your app at them.

This isn't something that just applies for frameworkless app building. This is generally good advice!

Performance of a frameworkless Scala app

Performance is relative, so to measure it I needed a benchmark. So as well as building the frameworkless version of this app, I built one to the same spec using the Scala tech stack I was using professionally at the time:

- SBT for building

- utest for testing

- http4s as web framework

That app didn't involve a front-end framework, but for completeness I chose to use vue.js as I'd dabbled with it already.

Build

I started by looking at cold builds - the full clean/build/test/assemble cycle, having to fetch all dependencies from remote. In the case of the SBT build, this meant clearing the ivy cache.

This turns out be almost comically unfair due to the sheer volume of dependencies pulled for running SBT alone - the frameworkless build took an average of 7.08s, the SBT build 10m 22.25s. To be fair, make is preinstalled, so I switched to having a prepared ivy cache which contained all the SBT dependencies, but I do think this somewhat serves to illustrate my point - why is this tool that bloated?

The following graph shows the durations of cold and warm builds for both flavours of app, across 10 runs:

Note that this is presented with a log scale - the average cold build time for the "unframeworkless" version using SBT was 178.86s, over 3 minutes, compared to 7.08s frameworkless.

Warm builds were much more comparable with an average of 6.35s frameworkless and 11.29s "unframeworkless".

The log scale does somewhat hide the wide variation in build time of the cold "unframeworkless" build, which varied from a minimum of 149s to a max of 211.76s - understandable when so many dependencies have to be pulled from the internet.

This leads nicely onto the size of the built apps. Both builds produce "fat" JARs which package up all the dependencies with the application code to make a stand-alone deployable artifact. The frameworkless todo.jar weighs in at 73K, the unframeworkless equivalent 48M.

Does any of this matter?

Probably not.

It isn't that often you do a completely cold build locally - the majority of times I encounter one is if a cache has been flushed on a CI server. If that happens a lot, it will start to get painful, but in my experience this is a rare and temporary situation.

73K vs 48M is a big relative difference, but in absolute terms 48M is nothing these days.

It's worth noting that this is an exceptionally simple app. A real world version would be significantly more complex, and build times would increase in both cases. My experience in Scala is that when using a framework like HTTP4S you are probably very bought into a whole ecosystem of related tools - this means both more dependencies and more complex / clever code, which can come with a major compile time hit. I suspect the build time would increase much more rapidly in the unframeworkless case, but can only speculate as I did not build a more complex app and don't have the figures to back that up.

Given that a faster building, smaller app does use less CPU and storage, there is an argument that it is greener as less electricity would be consumed in building, storing, and transferring it. A lot of people would have to be taking this approach for it to make a meaningful difference though.

Page Weight

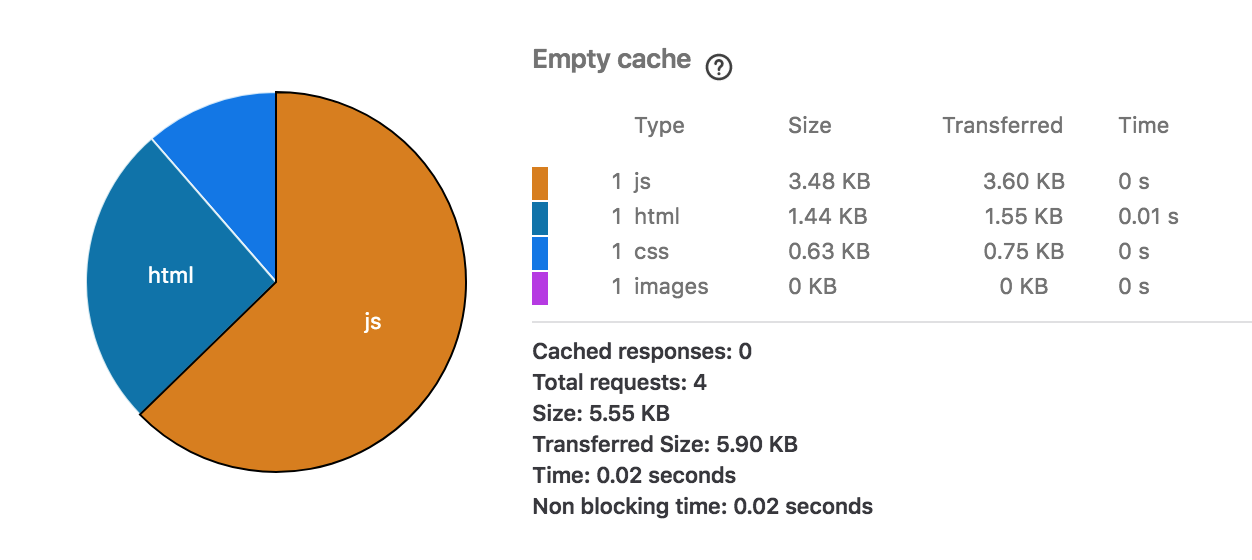

I won't go deep into this, as it touches more on the front end side than Scala app development. Below is a performance panel screenshot taken using Firefox for a cold load (empty cache) of the frameworkless version:

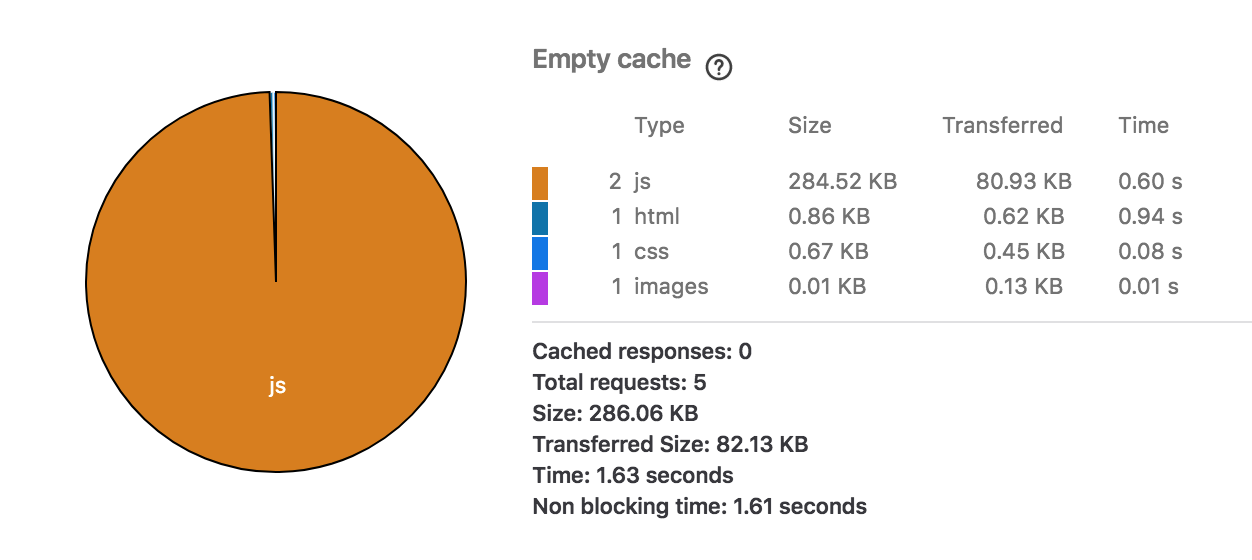

And the unframeworkless version:

The frameworkless version comes in at 5.5K, unframeworkless at 286K, the difference almost entirely down to the use of vue.js. Interestingly, the use of a frontend framework slightly reduces the size of the initial HTML payload, due to the way I implemented the frameworkless version by including an HTML template for TODO items within the page. Both versions can function without JS enabled.

The eagle-eyed will see a slight difference in size for the CSS response - this is down to HTTP response headers added by the web framework in the unframeworkless version.

Load

I attempted a stress test of both versions, but it didn't highlight anything that the page weight measurements from Firefox didn't already show. This is probably due to the low complexity of the sample app - it would be interesting to implement a data storage mechanism and stress test with that in place.

I suspect this is where the unframeworkless version might shine without some modifications to the frameworkless app, as those frameworks are more likely to already have mechanisms for handling high levels of concurrent requests built-in.

Security

Security is, or should be, usually a concern.

This very simple test app does not tell us much about security implications, so it's hard to be specific. Web frameworks do often come with helpers to help secure endpoints in various ways like facilitating CSRF or enabling features like CORS. When you get into these they are often not as magic as they sound, and implementing them yourself can be both easy and enlightening. While I didn't do it for this app, I have implemented both from scratch when using frameworks that didn't have available support at the time.

Of course, by using frameworks you will benefit from the discovery and closing of existing vulnerabilities - not doing so will mean being more vigilant, though this is not necessarily a bad thing.

Dependencies themselves are potential vectors of attack or vulnerabilities, as has been demonstrated more than once very publicly. Reducing dependencies reduces your attack surface.

Of course, do not roll your own crypto!

Conclusion

If there's a good reason to do this, it is learning.

Understanding the kinds of problems the frameworks and libraries we use every day are designed to solve, and the challenges faced in solving them, should help us understand how to work with them better ourselves. The potential causes of unexpected behaviour become clearer - and by understanding these fundamentals without reference to any framework, the learnings can be applied across frameworks. It helps to understand the fundamentals.

It should also give us a greater appreciation of the efforts of those who build the libraries and frameworks we depend on, which are usually open source and without extrinsic reward. You don't need to have seen many github issues to know these people take a lot of abuse from users, most of whom I would hazard to guess don't have a full understanding of the work involved.

There's also a sense of personal achievement that comes with it - frameworks can seem like magic, especially when you're a junior, and like Dumbo discarding the "magic" feather you can learn that really you are able to do this!

Would I do this in production? I don't think the day or so I spent on this, with the very limited scale of the app, really proves anything in that regard. My gut feeling is that it is doable, but you'd have to have the right context for it, with room for experimentation and psychological safety.

A common argument against would be that "people know how to use existing frameworks". I would contend that that is less important, and possibly less true, than you think - I've rarely seen two teams, even within an org, use the same framework the same way twice (or even, within a team, the same framework used the same way twice between apps!). It usually comes down to learning how a team makes use of a framework, and it's not uncommon to find they've written their own wrappers, even libraries, around this, which surely negates most of that argument.

I do think it would at least make a fun team-building and learning exercise, where that opportunity exists. Mob on it, and learn how your team can stand on its own, together!

A note on Scala

I used Scala for this, mainly because it was the language I was most using professionally at the time, and it of course has a bad rep. There's a lot of reasons for that which I won't dive into in this post, instead I will highlight the positive - Scala's terse, flexible, functional syntax made going frameworkless easier than I believe would have been the case with a great many other languages, once the Java API had been wrapped up and safely tucked away. Pattern matching with tuples and regexes to route requests looks pretty much like a routing DSL, but it's just basic Scala.

If you're keen on using Scala but tire of the arguably needless complexity of many of the frameworks, libraries, and tools that make up most of the ecosystem I highly recommend checking out the aforementioned Li Haoyi's stack, which extends to HTTP servers and clients inspired by Python.