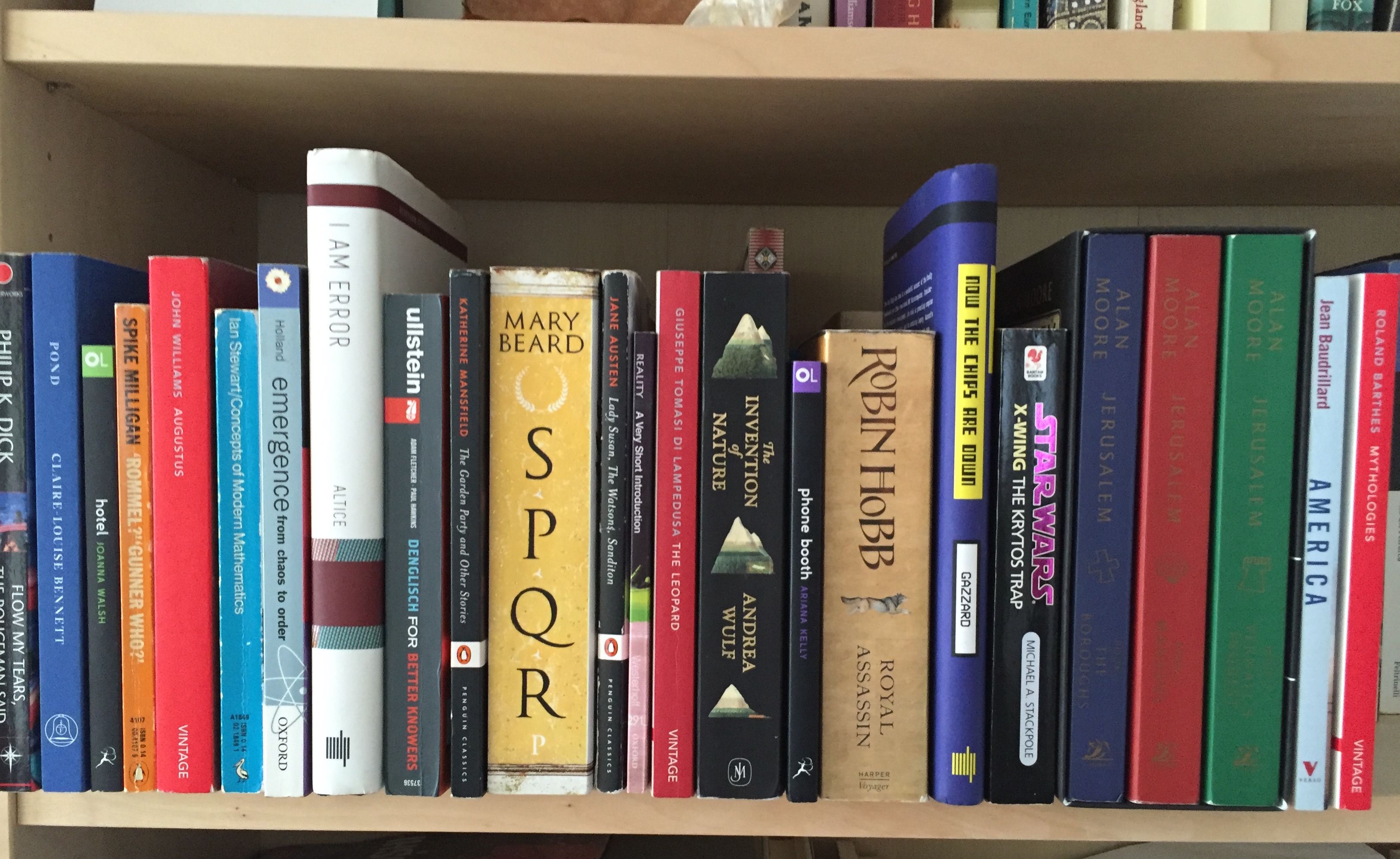

All the books I read in 2016

Well, all the prose books at least. I got through a fair few comics as well, but as that's a different medium I don't count them here. I'm working from memory, so if I give short time to the earlier entries it's due to my age...

This wasn't too bad a year, 22 books is obviously far from the target of one a week I've set myself for most of the last decade, but considering I had a hugely disruptive international removal and took on the task of reading Alan Moore's Jerusalem I think I did fairly well. Looking down the list now I have a feeling there's a bigger showing from women authors than usual, which is surely a good thing.

1: Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick

ISTR this started with what would ordinarilly be a decent paranoid high concept and then took a typically PKD reality-bending turn. I wasn't as engaged by it as by his best works (the previous one I read was A Scanner Darkly, a true masterpiece), but you shouldn't take that to be damning-with-faint-praise; it is still interesting, atmospheric and has some chillingly original moments.

2: Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

While I don't remember a lot of detail from this, I think it's more because the short stories (some very short indeed) have such similar themes and settings they have sort of blurred together in my memory. This isn't a criticism, though - they are very well written. An author I will be keeping a look out for.

3: Hotel by Joanna Walsh

My favourite entry so far in the Objects Lessons series, this one combines the usual examination of a specific topic (Hotels) with something more personal as the author's relationship breaks down. Some great insights and excellent writing, Joanna Walsh is another author I will be looking for more to read from.

4: "Rommel?" "Gunner who?" by Spike Milligan

I started reading Milligan's excellent war memoirs the previous year after finding a bunch in my local second hand bookshop; your mileage will vary according to whether you like his sense of humour, but I have been finding them brilliant, very funny, often poignant and even informative.

5: Augustus by John Williams

The last of the three big JW novels I have gotten to, and yet again a big contrast. I have seen it written that you would not guess they had the same author if you did not know, and while I see where that is coming from I think you could; this has many parallels with Stoner at least, especially towards the end. The epistolary format (one of two books in this style I read this year) works very well not only for getting across political machinations but also character. A nice companion piece to the Claudius novels, even if they don't dovetail in their fictionalisations of all the characters.

6: Concepts of Modern Mathematics by Ian Stewart

Another second-hand-bookshop find, this is a broad introduction to modern mathematical concepts (albeit from the 1970s), and an early work by the now well-known Ian Stewart. A lot of it was reinforcing things I already knew, though I admit it occasionally went over my head as well.

7: Emergence: from chaos to order by John H. Holland

I have to admit, I don't remember this well at all. ISTR it was largely the author proposing an approach to analysing emergent properties and it didn't grab me in the way I expect of a popular science book however convincing his arguments were.

8: I AM ERROR by Nathan Altice

One of the best entries in the Platform Studies series so far, and having never owned an NES (or even played with one as a child) I am not coming at this from a position of nostalgia - this is a well-informed, thorough, fascinating and entertaining study and history of the game platform. The best of these books always make me think how fateful the decisions I make as a software engineer might be in terms of ultimately affecting the business and those working for it, and I find that's an important take-away.

9: Denglisch for Better Knowers by Adam Fletcher and Paul Hawkins

A gift from a colleague after I transferred to Berlin and started learning German, this is an entertaining bilingual book about some of the quirks of the German language (and by extension, culture). I do like to hedgehog myself on occasion.

10: The Garden Party and other stories by Katherine Mansfield

I have to admit only a couple of individual stories stuck in my mind at all, though I do seem to recall enjoying this at the time.

11: SPQR by Mary Beard

Excellent work from a reliably good educator on classical matters. People often like to claim how differently people thought historically to how they do today, but I am often unconvinced and this brought ancient Romans to relatable life very well for me. I vividly recall reading this while on a plane arriving in England on the morning of the EU referendum result, and there was a saddening paragraph on the Roman electorate's distrust of vested interests. If only the modern electorate could be so discerning.

12: Lady Susan, The Watsons, Sanditon by Jane Austen

Lady Susan is the second epistolary work I read this year, a witty early novella about the machinations of the widowed title character who is manipulative, deceitful, self-serving and yet remarkably likable; she was brilliantly brough to life by Kate Beckinsale in the movie Love and Friendship last year (the fact that I read it in the same year is pure coincidence, I had no idea there was an adapatation coming). The other two works here are unfinished fragments. The Watsons felt polished but quite downbeat, whereas Sanditon felt more like an early draft and I had problems following the characters at moments; there was something to it though, and it could well have been a classic if Austen had lived to complete it.

13: Reality: A Very Short Introduction by Jan Westerhoff

A good overview of the subject, which after all is the purpose of these books, but I didn't feel like I learned a lot from it.

14: The Leopard by Giusseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa (trans. Archibald Colquhoun)

One of those classics I should certainly have read sooner, and one of the rare occasions these days I feel I will re-read something. The language is beautiful even in translation, I can only imagine what it is like in Italian, and it does nothing to dim the love I've been nurturing for Sicily and Southern Italy in recent years.

15: The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science by Andrea Wulf

Humboldt is one of those names that I knew but couldn't attach to any historical person; it seems I am not alone as there are few people in the world with so many (and so many diverse) things named after them that it is unlikely you haven't heard his name. This is one of those special biographies that completely drew me in and convinced me that more people should know about it's subject and his work. Well-written and deserving of the Royal Society award it took (and not of the unfortunate criticism by someone who should have known better).

16: Phone Booth by Ariana Kelly

Another good entry in Objects Lessons, though without the personal touch that made Hotel so compelling. I can't think of much to say about it, as it does exactly what it should, well.

17: Royal Assassin by Robin Hobb

I read the previous one something like 9 years before; the gap isn't due to a dislike, I just never felt the compulsion to read a fantasy novel brick in the meantime and like many such trilogies (especially debut ones) the first installment is self-contained enough. This is clearly a middle-book, but it is remarkably compelling despite the trad. high fantasy tropes, cringe-worthy romance and sometimes clunky writing. I am probably not selling you on this, and if you don't like this sort of thing it won't change your mind, but I found it quite a page-turner.

18: Now the Chips are Down: The BBC Micro by Alison Gazzard

Aside from the short-lived Texas Instruments TI-99 we had at home, the BBC Micro was my early introduction to computing; I can remember the computer room(s) of lower secondary school more vividly than the form rooms and have fond memories of the likes of Martello Towers (sadly not mentioned here) and constructing pixel art by laboriously setting memory addresses. This is a good examination of both the machine and the social context that enabled it. I was heartened to find that a number of the people and companies whose stories are told here continued in the computer industry to the present day with some succes.

19: Star Wars: X-Wing: The Krytos Trap by Michael A. Stackpole

I don't believe in guilty pleasures, but if I did... I have a strong attachment to the now-decanonised Star Wars EU (surely there's a Brexit joke in there somewhere) after the Timothy Zahn novels reached me at a tender age, and in recent years have been going through some of those old ones from the 90s that I missed, especially the X-Wing series. Noone would argue this is great literature (exposition dumps abound, everybody is always frowning), but they capture the feel of Star Wars well and are a compelling way to pass some leisure reading time, especially between more weighty/serious books.

20: Jerusalem by Alan Moore

Speaking of weighty... I'll skip straight to the TL;DR (for most people this book will be TL;DR) - I thought it was very, very good, but not without its flaws.

First of all, yes, it is a big, dense book; 1280 pages split over three books with quite a high word-count-per-page. There are plenty who have criticised it for this, but I actually don't feel that. There is a lot of information here, a lot of fine detail, and the book would be poorer without it. Secondly, anyone familiar with Moore will know one of the main criticisms of his work is his use of rape as a plot device, and this book is no exception. In fact, it's fairly central and is my main source of discomfort. Finally, though it could be clunkier, it feels like more characters than you would normally credit are amateur local historians who muse frequently on the area they grew up in; this is made more forgivable due to one of the purposes of the novel (as expounded in the novel itself) being to stop these details being forgotten which otherwise so easily would.

Problems aside, though, this is a remarkable, ambitious piece of work. You could come away from it convinced that a small area of a little thought about Midlands town is absolutely central in the history of western civilisation (maybe it is) and it delivers Moore's ideas about life and art very effectively. The mythology of the novel is extremely well constructed and fascinating and there is some compelling imagery (though in spite of Moore's comic background, the novel is definitely the right medium for this. I can't imagine it being successfully adapted to any other).

I felt like I lived in this book for a couple of months (I never wanted to skim it or miss something through being tired, so I took my time), and missed reading it once I had finished. Very glad to have put the effort in here.

21: America by Jean Baudrillard (trans. Chris Turner)

This had been on my to-read list for I don't know how long; it does occasionally veer too close to pretentious / obscure post-modern language, but when it is at its most lucid there are some fascinating observations about America and, in contrast, Europe.

22: Mythologies by Roland Barthes (trans. Annette Lavers, Siân Reynolds)

Another long-standing member of the reading pile, and not unrelated to the previous book. Again there are fascinating observations in the many short essays here, occasionally undermined by pretention / jargon. For all that it was written 60+ years ago, the observation about how female authors are, in contrast to male authors, almost always described in terms of their family situation felt almost contemporary. The longer essay towards the end of the book which is supposed to expand on his ideas here was near-unreadable for me though.